Preparing Our Island City and its Bioregion for A Bright Green Future

November 23, 2013

Dear Colleague:

I am writing to invite you to join me on a great journey, likely the most crucial and transformative adventure of our time. I invite you to participate in a rebirth, not only of a great urban center – New York City – but also of the spectacularbioregion that surrounds and supports it.

We live in dangerous times, when economic collapse, climate chaos, and peak oil threaten the foundations of society, abundance, and all we hold dear. “Business as usual” will no longer suffice, because that way leads to certain pain, peril and impoverishment. The more visionary path, to A Bright Green Future, will be far more challenging. It is a road we must build as we walk it.

So I invite you to come, talk, debate, and delve into the possibilities, the roots and routes of that new way – to explore A Bright Green Future for the New York City Bioregion. Let’s build a pathwhere the shortsighted goals of “growth” and profit are supplanted by the goals of resilient economic prosperity, social justice, and human and ecological health.One in whicha stumbling global economy is replaced by a sure-footed local economy and a local food system that can support and feed us through a challenging time of transition where we learn to trust and count not on banks or government, but on each other.

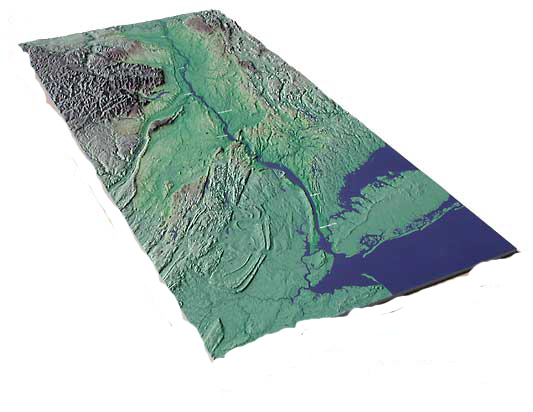

As the NY/NJ Baykeeper, I learned to see the New York City Bioregion not as a collection of states or towns, competing industries or interests, but as a unified place. When seen from space, our Bioregion is without seams. The inland mountains and low hills feed thousands of tributaries, which feed our magnificent estuary and the sea. Our Bioregion is one abode – one people that has forgotten its roots and lost its identity. I invite you on a journey to find ourselves, to rediscover the great power of bioregional unity. Your strength, your energy, and your visionis needed now more than ever.

Sincerely,

Preparing Our Island City and its Bioregion forA Bright Green Future

Executive Summary:

We are living in an age of unprecedented violent change, where three highly disruptive crises – global economic instability, climate change, and peak everything are converging insidiously to shred the fabric of society. The coming shocks: international financial collapse, epic flood and drought, energy and natural resource shortages, and extreme price spikes are likely to be catastrophic if we do not prepare. The New York City Bioregion is especially vulnerable to these disruptive changes. With one of the world’s greatest ice-free harbors on earth, New York City was built on global commerce. But today, the far-flung network of international trade that once pumped vibrant economic life into our communities threatens to collapse as imported natural resources along with the fossil fuels needed to transport them become increasingly scarce and expensive.

New York City, being an island metropolis, is also projected to be one of the five U.S. cities hardest hit by climate change and most vulnerable to rising sea levels. Likewise, our metropolis produces little of its own food and little else for its people’s basic needs. This puts our city and its surrounding communities in serious jeopardy. The impacts and recovery from the “new normal” super storm Sandy are unfolding as I write.

First estimates say Sandy’s costs could top $70 billion. But that’s nothing compared to the deaths caused directly and indirectly by the storm, the suffering of 8 million left without power; tens of thousands left homeless; seniors, the sick and children forced into evacuation centers. Compare that $70+ billion price tag now with the more modest $10-15 billion to construct wetlands and oyster reefs, enforce flood hazard building restrictions, plan for a retreat from flood hazard areas, and appropriately place sea gates needed to protect New York City’s vulnerable infrastructure. Other major cities around the world have implemented these protections but not here. And don’t expect the Tea Party Congress to protect us. They won’t vote for “more government” to mitigate climate change or even harden our infrastructure or our energy, transportation and communication systems against an unimaginable future we know is coming. So much for “National Security.”

What is certain is that these already rapid, violent changes are accelerating. With government, big business and the media doing little to address the unfolding crises, the opportunity to make our Bioregion more resilient in this time of turmoil could easily be lost. We must act now.

Of course, the critical and immediate question is – what, exactly should we do: How should the New York City Bioregion respond productively to the end of cheap oil and the failure of our “growth at any cost” culture? How can we act proactively to rising sea levels, and less abundant, more costly natural resources including oil and food? Also, how do we finance the dramatic enhancements that must be made to the natural and human landscape for our Bioregion to survive and prosper? Finally, how can you and I, and other private citizens, join together to hospice the decline of the current system, and midwife the vital transformation into A Bright Green Future for the New York City Bioregion?

It is long past time to gather the brightest most committed people from all parts of the New York/New Jersey/Connecticut/and Pennsylvania bioregion for a charrette, an open space dialogue and analysis, to discuss the best, most pragmatic route to a better future for our communities. Working together, we can develop a blueprint, an implementable comprehensive plan based on vibrant sustainable, slow money, small business, main street economy, focused on local energy and local food, with all of the resulting positive economic, social, and environmental outcomes. The participants in this great gathering must be many, varied and inclusive. We must invite entrepreneurs and social venture capital investors; planners and co-housing/eco village developers; Transition Town advocates, Permaculture practitioners and foodshed advocates; charitable foundation directors and futurists; students and union members; fishermen, environmentalists and economists; organic and biodynamic, rural, suburban, and urban farmers; academics, government officials, and local business people. All points of view will be needed to come up with implementable visionary ideas that can lead us safely through the impending crises and into A Bright Green Future.

The two seminal questions for the first proposed charrette will be:

1. How can the New York City metropolitan areacommunitydevelop a food security plan to feed itself from farms within 100 miles of the Battery? Connecting New York City, not just to its watershed but to its “Foodshed.”

2. Should we commit $10-15 billion to construct wetlands and oyster reefs, enforce flood hazard building restrictions, plan for a retreat from flood hazard areas, and appropriately place “hard infrastructure” needed to protect New York City, coastal New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut’s vulnerable infrastructure?

Luckily, we needn’t start from scratch. Many in our region have thought hard on these issues, and begun to puzzle out solutions. The global Transition movement also offers us important models for local sustainability, and represents a promising way of engaging people and communities to take the far-reaching actions necessary to move beyond peak oil, climate change and economic crisis.

Though the path ahead may seem daunting, it is important to remember the past. Not so long ago, New York City and its Bioregion fed itself. Daily, wagon loads of produce rumbled from farms, along dirt tracks to ferries, and fishing boats docked at wharves bringing seafood, meat, vegetables, milk, rum, cheese, and apples to Manhattan markets. The New Economy we create for our bioregion will likely resemble in some ways that diverse and prosperous regionally self-sufficient economy.

Our Bright Green Future will re-create self-sufficiency for the New York City Bioregion, with a mutually supportive connection to the surrounding New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut farms, fisheries, communities and the bounty of preserved wetlands, forests, mountains, bays, and the sea.

Time is short. If we are to be the designers and stewards of our community’s future we must move quickly and decisively to begin shaping the transition of the New York City Bioregion.Together we can seed a post-growth/post-carbon economy that serves and benefits all people and all of nature, a bio-regional re-localized economy based on renewable resources harvested at nature’s rates of replenishment.

I look forward to your response and feedback to this proposal, and to your participation in one of the greatest adventures of our time, as we seek to make a better life for ourselves, our families, and communities.

Preparing Our Island City and its Bioregion for A Bright Green Future

The Perils We Face: Hospicing the End of One Era and Midwifing the Start of the Next

By what name will future generations know our time? Will they speak in anger and frustration of the time of the Great Unraveling, when profligate consumption exceeded Earth’s capacity to sustain, and led to an accelerating wave of collapsing environmental systems, violent competition for what remained of the planet’s resources, and a dramatic dieback of the human population? Or will they look back in joyful celebration on the time of the Great Turning, when their forebears embraced the higher-order potential of their human nature, turned crisis into opportunity, and learned to live in creative partnership with one another and Earth?[i]

Our world is now convulsed by three great converging crises: global climate change, global economic instability, and peak everything – a drastic decline in the availability, and escalation in the cost, of nearly every resource, ranging from oil to rare earth metals. Add to these principal threats the risks of overpopulation, wars over natural resources, the total failure of aging and overstressed infrastructure, the erosion of traditional community values, declining biodiversity and the sixth great extinction. Any one of these dangers could bring down a civilization, and taken together, pose a formidable challenge.Each of the big-three crises presents particularly thorny problems for the New York City Bioregion:

Climate Change: The record-setting Arctic meltdown, intense drought of the summer of 2012; the 300+ months in a row of hotter than average temperatures; and the new analysis of global warming and extreme weather by NASA climatologist James Hansen are a sobering reminder of where we find ourselves on the climate change timeline. Scientists have now drawn a clear connection between rapidly accelerating Arctic warming, the slowing of the jet stream, and extreme disruptive weather around the world. Remarkably, the severe climate upheaval we are experiencing now is the result of just 1.4 degrees Fahrenheit global warming in the 20th century and a loss of just half the summer Arctic ice cap. Looking ahead on the timeline, we are on course for more than 9 degrees of global warming by 2100, with a total meltdown of the summer Arctic ice sheet projected for between 2015 and 2030. The effects of these fast moving events are unknown, but likely to include huge negative impacts on global commerce, industrial agriculture, and sea level rise. New York City is among the top five U.S. cities likely to be most negatively hit by climate change for a variety of reasons: a warming North Atlantic Ocean means that high-powered storms like Hurricane Irene could become far more numerous; that regular storm surges could overwhelm critical infrastructure ranging from airports to subways, bridges and roads; that epic droughts could threaten our drinking water system and far-flung food supply. And the incomprehensible tragedy caused by the “new normal” super storm Sandy must be the wakeup call the Bioregion needs to pound these indisputable facts into the head of the “deniers.”

Economic Instability: The “old” economy of the last hundred years is proving to be a flimsy house of cards, sustained by the illusion that our financial system can operate without ecological, economic, or social limits or foundations. The dangerous delusion of “progress”, that our economy can only function when it is “growing”, is perpetuated in the speeches of the President, Treasury Secretary, Chairman of the Federal Reserve, and politicians, candidates, and pundits of all stripes. However, the 2008 housing bubble collapse, the meltdown of big banks, big insurance, and Wall Street all made it abundantly clear that money does not equal wealth. Still, New York City remains largely dependent on, and vulnerable to the wellbeing of the financial industry for its prosperity. This is a serious problem. Any number of future financial shocks, brought on by a collapse of the European Union, or by a major Middle Eastern War, or any unforeseen economic panic, could shatter Wall Street and big finance, toppling the dominoes of the New York City financial, real estate, insurance, restaurant-hotel, port, tourism, and service industries.

Peak Oil and Peak Everything:Richard Heinberg in his book Peak Everything[ii] describes how unprecedented population growth; energy consumption; food consumption; an unparalleled shift from a rural to an urban population; and the impacts of humans on the environment are bringing on an imminent catastrophe. As others have done, he postulates that the 21st Century ushered in an era not only of unprecedented population growth, but of world-wide declines: Oil, natural gas, uranium, and coal extraction; arable farm land; yearly grain harvests; climate stability; economic growth; ocean fisheries; freshwater; glacial and polar ice; and minerals and ores are all fading. The New York City Bioregion is connected tenuously to the rest of the world by literally thousands of lifelines, including an aging and increasingly failure-prone power grid; an aging and leaky water system; and a vast network of roads, rails, shipping and air routes that rely exclusively on increasingly costly fossil fuels. Like a patient on intravenous life support, any major interruption in the flow of natural resources, energy, water or food to the metropolitan area could hamstring or permanently harm its economy and people. With global oil, gas and coal production predicted to irreversibly decline in the next 10 to 20 years,this collapse becomes not a question of if, but when.

All three of these great calamities were born out of the world’s profligate use of cheap, non-renewable fossil fuels. Like so many past boons, this one has now become a bane. It’s important to understand that all three crises are intimately linked to each other, and magnify each other: For example, a severe drought, like this year’s in the Midwest, could cut off our region’s supply of wheat, corn and soy, causing food shortages and a financial meltdown. Peak oil requires that we drill for fossil fuels in increasingly extreme landscapes, like the deep-water Gulf of Mexico, prone to more and more powerful hurricanes, or by using hydraulic fracturing that will likely contaminate groundwater in the heart of New York and Pennsylvania farming. Our sprawling global oil pipeline stretches halfway around the globe, making us vulnerable and dependent on volatile states. An economic crash or financially-sapping resource war abroad, could wreck our balance of trade, and shatter our tax base, making it fiscally impossible to harden our infrastructure against climate change impacts, which would lead to more economic disasters. The accumulation of shocks could be catastrophic, if we do not prepare.

Faced with a future jeopardized by a rapidly changing and hostile climate; a disrupted economyregularly careening toward financial collapse; and an energy infrastructure based on declining and costly supplies of oil and other non-renewable fuels; there are four possible response strategies, according to Heinberg those strategies are:

- Denial – waiting and hoping that some unforeseen miracle will solve the problem;

- Last One Standing– global competition and warfare to control all remaining resources;

- Power-down – global cooperation to reduce energy use, conserve and manage resources, while reducing population; and

- Building Lifeboats – preparing local areas to be sustainable in the event of a global economic and environmental collapse.[iii]

Enumerating the daunting challenges that face civilization, it’s easy to conclude profanely: “No, seriously folks, we’re SCREWED!” But I argue otherwise and optimisticallyin this paper: “Yes, things are bad. I mean bad – REALLY bad. But we are only SCREWED if we stick to the old paradigms of growth at any cost, the economics and institutions of big finance, big agriculture, and the multinational corporations that serve them.” I suggest a very positive, very different, alternative course of action for the New York City Bioregion, one that flows from the following ideas:

- The inevitable decreasing availability of cheap fossil fuel will eventually make the transportation of food over long distances economically unfeasible, and the phrase “local food” will acquire an urgent, vital meaning beyond the current limited lifestyle implications. Local food will become less about maintaining eco-correctness and more about whether we’re going to have enough to eat! That’s why this proposal for A Bright Green Future puts so much emphasis on local food.

- Most past discussions about making the New York City Bioregion more resilient focused on climate change by either lessening our contribution of greenhouse gases or adapting to future effects. Government’s response to global warming while urgently needed has so far been negligible. Experts agree that New York City will be one of the five U.S. cities most affected by climate change.[iv] Manhattan Island, with its large population, extensive coasts, vulnerable underground utilities and transportation systems is at risk to flooding and sea level rise. That’s why this proposal must face the functional realities of climate change without flinching.

- New York and its metropolitan area are connected to and thoroughly dependent on vulnerable infrastructure: grids and networks, pipes, electrical transmission lines, highways, rail, bridges, tunnels, and shipping systems to provide fuel, power, water, food, and consumer goods. That’s why this proposal for A Bright Green Future includes a re-localization and an energy descent planning process, to prepare for the revitalization and maintenance of vital infrastructure.

To adapt to a profoundly differentpost carbon world, we must begin now to make radical changes in our attitudes, behaviors and expectations. This is a “Sisyphean” task, but one that we can pursue with hope and extreme optimism:

“It’s useful to contemplate a best-case outcome. The economy of the future will necessarily be steady-state not requiring constant growth. It will be based on the use of renewable resources harvested at a rate slower than that of natural replenishment; and on the use of non-renewable resources at declining rates, with metals and minerals recycled and re-used wherever possible. Human population will have to achieve a level that can be supported by resources used this way, and that level is likely to be significantly lower than the current one.”[v]

This document explores our Bioregion’s response to the end of cheap oil and the “growth at any cost” culture. It confronts the question: How can we hospice our current era’s decline, and midwife its transformation to a new Golden Age. The ideas presented here have grown out of my career as a planner and environmental advocate; out of books and papers I have read, conferences and lectures I’ve attended, and Transition[vi] and Permaculture[vii] certification workshops in which I’ve participated.

I invite you to read this paper not as a passive observer, but as an active player in the creation of A Bright Green Future for the New York City Bioregion. Please understand: inaction is not an option. Each of us will be forced to engage in this great transformation – to take a position on our future whether we wish to or not. I hope you’ll want to imagine, design, and implement a plan to create bio-regional resiliency and abundance. Let’s begin to craft a viable vision for the future of the New York City Bioregion. Is this a daunting endeavor? Yes. Is it absolutely necessary? Yes. Is it now or never? Yes.

Building the Road We Will Walk On

Our central survival task for the decades ahead, as individuals and as a species, must be to make a transition away from the use of fossil fuels and to do this as peacefully, equitably, and intelligently as possible. [viii]

New York City and its metropolitan area (The Bioregion) are at a crossroads. We have vital choices to make immediately between “business as usual” or “A Bright Green Future.”[ix] Looking forward rationally at all the indicators – looming peak oil, climate change, and global economic instability – the “business as usual” choice takes us down a road to cataclysmic energy shortages and infrastructure failure, to inundation from sea level rise, to financial meltdown and its attendant social disarray.

Choosing sustainability is a first vital step away from “business as usual,” but only the first step leading us to true Transition. To become a working Bioregional community, we will have to relearn to survive and then thrive on our own resources, to create a democratic, fair and equitable society in which both people and nature benefit. The choice is ours, but it must be made now. If we wait, the window of opportunity will close. This paper is a call to action, to begin now to create a bold vision, a pragmatic, implementable, and inspiring strategy for A Bright Green Future for the New York City Bioregion.

When a small group of us started NY/NJ Baykeeper in 1989 we developed just such a big vision. Despite the Harbor’s challenging condition, we articulated a plan to create an urban Eden by the Bay, circled by public parks, promenades and greenways. We foresaw a clean harbor where fresh oysters and clams could be harvested for the tables of local restaurants. Our Harbor/Estuary would be a cherished destination for families – a swimmable, fishable, boat-able, beautiful landscape of rivers, wetlands, beaches and bays – a national treasure where any child could see a soaring great egret. Ours would be a region of revitalized communities, with poverty replaced by economic opportunity, where people are empowered, and government serves our needs not the needs of special interests. Ours would be a community that connects us together, feeding us economically and spiritually.

As a result of more than twenty three years of community organizing, advocacy, and when called for, litigation, a significant part of that vision has been realized – the entire Hackensack Meadowlands has been preserved and is being restored.Liberty State Park, the Hudson River Park, and the proposed East River Greenway are the genesis of a string of green gems on an otherwise urban waterfront. New York City has adopted green infrastructure to manage storm water and combined sewers.The Port Authority and the states of New York and New Jersey have spent millions to preserve urban open spaces.Unencumbered access to the waterfront has become the norm: kayakers, swimmers, and fishermen are ubiquitous. There is a Harbor-wide oyster habitat restoration project that successfully partners federal, state, and local governments and non-governmental organizations. And the Passaic and Hudson Rivers are being remediated and restored. Best of all, an engaged and informed citizenry has come to think of the “Bays of the Harbor” as theirs.

A Positive Vision for a Resilient and Abundant Future

Baykeeper’s plan for the region, as farsighted and successful as it was, did not go nearly far enough. What we need today is an inspired revolutionary vision of a New York CityBioregion that goes beyond the Bay and its shorelines, that includes surrounding communities and an extensive urban and rural agricultural farmshed. What is needed too is a pragmatic relationship with local food producers and reuse of all resources through sustainable design and careful management.

This vision for A Bright Green New York City Bioregion is built on three pillars:

• Resilient economic prosperity

• Social justice

• Human and ecological health

A society built on these three pillars will produce the highest possible quality of life in the best possible environment. A pragmatic agenda of programs and policies to advance these goals must be responsive to the finite limits of ecological systems, while fostering the limitless opportunities of democracy in which all people are able to contribute their ideas and effort, and develop to their fullest potential.

Resiliency means dynamic abundance, not static scarcity. If we apply our collective ingenuity in a comprehensive planning process, it is possible for our social and environmental goals to be transformed into ecological improvements and economic opportunities. A vision of a resilient and durable future includes a market for creative entrepreneurs, motivated by enlightened self-interest. The future is not something to be feared or fought over – it is something we can build creatively and cooperatively. We can work together, live better, and waste less.

Any plan for a resilient bio-regional economy must insure that everyone has fundamental needs met as a non-negotiable condition. At a minimum, people’s needs include nutritious food, shelter, healthcare, education, and ecosystem services[x] – all provided affordably and reliably.[xi]

Re-development for resiliency will be a process of continuous improvement by design of natural, built, economic and social systems. This means that we must craft variety and productivity into natural systems; increasing efficiency; using renewable resources and eliminating all waste in built systems; employing social and environmental goals to create market opportunities in economic systems; making a priority of educating all citizens about whole systems[xii] and natural capital,[xiii] and providing the channels to act on that knowledge. In order to accomplish this arduous strategy we must find the means to:

Provide the same level of service with two to ten times less resource use.

- Stretch every gallon of water, joule of energy, and pound of materials further to meet fundamental needs.

- Use every available alternative energy technology – solar, wind, and tide – to produce local energy while wisely using dwindling fossil fuels to nimbly achieve this transition.

- Fund and implement pilots for carbon neutral “grid free” communities and neighborhoods by using the Danish Island of Samsoe[xiv] as a model.

- Design and use products for continuing streams of service and value, not obsolescence.

- Establish protocols for labeling products, buildings, and other infrastructure with disassembly and re-manufacturing instructions.

- Promote the use of waste as a resource in eco-parks to cascade multiple uses for water, energy, and materials through waste exchanges.[xv]

- Make capital improvements as needed to provide a commercially viable form of waste (i.e. the separation of organic waste to convert it to compost and energy).

- Cultivate and support businesses that adhere to all of these principles through a tax shift.[xvi]

A Bright Green New York City Bioregion may sound like an Ecotopian [xvii] vision, but if that is what is required to provide healthy abundance to its inhabitants, without consuming more resources than it produces, without creating more waste than it can assimilate, and without being toxic to itself or neighboring ecosystems – so be it.

The ecological impact of the Bioregion’s inhabitants will reflect the basic principles of planetary supportive lifestyles. Its social order will reflect fundamental principles of fairness, justice and equity. Any implementable plan for A Bright Green New York City Bioregion must be modeled upon, and magnify, the self-sustaining resilient structure and function of natural ecosystems. If we can agree on a way forward, and cooperate, our bioregion can thrive in a time of global crisis.

A New Economy to Power A Bright Green New York City Bioregion

The “new” New York City Bioregion will prosper through an eclectic amalgam of business, nonprofit and government innovation, including: rooftop solar warehouses, wind farms, and tidal energy producers; urban and rural farmers, and rooftop apiaries; commercial fishermen, fish mongers, and fish farmers; local farmers markets, shoreline farmers and seafood markets; a local water-based transportation system to bring goods to market; suburbia converted to interconnected “front yard” farms; a local currency used to pay for local commodities; buying and hiring locally; restored and created wetlands providing nurseries for fish and wildlife and where blueberries and other produce can be sustainably harvested; sustainable forests that are logged selectively with an eye on future production; public works projects such as sea walls and sea gates as required to protect communities and valuable infrastructure against sea level rise; an economy of local businesses and micro-industries, including everything from brewers and butchers to cheese makers to toolmakers; from ship builders to bicycle manufacturers; local wind turbine, solar collector, and tidal generator manufacturers and installers; shoemakers and fix it shops; composters and oil recyclers – all well supported by a New Economy.[xviii]

This New Economy is not completely new. It will resemble in fundamental ways the regional vibrancy, diversity, self-sufficiency and prosperity that our Bioregion once enjoyed. It will be inclusive, inviting citizens, businesses, entrepreneurs large and small, non-governmental organizations, and government to play an equal cooperative role. Our Bright Green Future will re-create self-sufficiency for the New York City Bioregion, with a mutually supportive connection to the surrounding New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut farms, fisheries, communities and the bounty of preserved wetlands, forests, mountains, bays, and the sea.

We will implement the goals of this New Economy by applying the common sense Permacultureethics of care for the earth, care for people, and fair share – and by application of P.A. Yeomans’[xix] functional relationship analysisto map, examine, and analyze the Bioregion’s climate, landform, water, access and circulation, micro-climates, vegetation and wildlife, buildings and infrastructure, zones of use, soil fertility and management, and aesthetics and culture to give us the basic information we need to plan for and implement the components of A Bright Green Bioregional transformation.

The New York City Bioregion’s New Economy needs to:[xx]

- Operate as a self-contained economy with resources found locally.

- Be carbon-neutral and become a center for renewable energy production.

- Achieve a well-planned regional and local transportation system that prioritizes movement of goods and people as follows: walking first, then cycling, public transportation, and finally private and commercial vehicles.

- Maximize water conservation and efficiency of energy resources through conservation.

- Design and construct a zero-waste system.

- Restore environmentally damaged urban areas by converting brownfields to greenfields.

- Ensure decent and affordable housing for all.

- Improve job opportunities for disadvantaged groups, and allow seniors and young people to play useful and meaningful civic roles.

- Support local agriculture and produce distribution.

- Support cooperatives and worker-owned commercial and manufacturing enterprises.

- Promote voluntary simplicity in lifestyle choices, decreasing material consumption, and increasing awareness of the environment and sustainability.

In the early 1970’s, I was one of those “head for the hills” people who thought that I could insulate and isolate myself and my family from increasing social and environmental problems. I am no longer that person. I now see our single best hope in unity. I see the answer to the unfolding crisis not in each person becoming more independent from society, but rather in the transformation of society itself, to achieve mutually beneficial cooperation – forging local/regional levels of interdependency and self-sufficiency through local energy generation, local food production, local manufacturing, and the building of resilient interconnected communities that supply each other not just with the basics of life, but a vital regional culture.

It is easy to be disheartened by the dark side of a future where climate change, global economic instability and peak everything will play such a major role in our daily lives. So, how are we to live in such a moment with positive intention and hope? How can we act on our commitment to life, our children and the common good? If our Bioregion can embrace a resilient path and invest in it now, we have a good chance of survival and adaptation to the challenges that lie ahead.

Food and the City

As daunting as the challenges and predicaments outlined [here] may seem, the good news is that we already have everything we need to create a better future.All the understanding, resources, technology, ideas, system, institutions, and thinking are already available, invented, or in place, ready to be deployed in service of a better future; we just need to decide to make use of them. By simply reorienting our priorities, we can simultaneously buy ourselves time and assure that we choose prosperity over growth. – Chris Martenson[xxi]

If we take Chris Martenson’s cautionary but optimistic challenge seriously, it is high time we got down to the business of literally and figuratively cultivating the fields of the future. Our arduous task is to support re-localization, redefine the logistics and trajectory of food sustainability, and promote alternative economic development in a post carbon New York City Bioregion.

Author and economist Michael Shuman[xxii] has investigated the potential economic impacts of food localization. Recent research conducted by Shuman in Colorado, New Mexico, and Northeastern Ohio suggests that investment in local “food-sheds” can substantially increase both demand for, and supply of local food creating thousands of new jobs, generating hundreds of new businesses, and producing millions of dollars in revenues to support the local economy.

Shuman’s 2010 Cleveland study[xxiii]found that 25 percent food localization by the year 2020 would result in more than 27,000 new jobs. It would also generate $4.2 billion in economic activity, $868 million in addedwages, and $126 million in state and local tax revenues – each year.

In a study for Transition Colorado,[xxiv] Shuman found similar economic benefits. He determined that a 25 percent local food shift in Boulder County (including the City of Boulder) would create 1,680 jobs with wages of $82 million, new economic activity of $137 million, and $12 million in Taxes.

Using Shuman’s findings to inform the next steps of our own Food Localization movement, we could create a detailed strategic and economic plan for food localization in our own Bioregion now.

“Agriculture within [the San Francisco] “foodshed,” as it was defined for the purpose of this study, produces 20 million tons of food annually compared with annual food consumption of 935,000 tons in San Francisco and 5.9 million tons in the Bay Area as a whole. In all, more than 80 different commodities are represented, only a few of which are not produced in enough abundance to satisfy the demands of the City and Bay Area: eggs, citrus fruit, wheat, corn, pork and potatoes. Many other commodities are available only seasonally, even though northern California has a long growing season.”[xxv]

Local food is distinguished not only by where it originates, but also by who produced it and how. New York City has developed Plan NYC[xxvi] and the City Council has passed legislation supporting local food use in City institutions. This program is in the earliest stages, but there are academics[xxvii] and non-profits that are advising the Council and advocating for a more comprehensive local food policy.[xxviii]

The City Council has approved and Mayor Bloomberg has signed laws that support a diverse number of local food initiatives including: the Watershed Agriculture Council – NYS Food Purchasing Law; local food incubators (La Marqueta); a Food Systems Metrics Law; the Hunts Point Market Redevelopment as a Food Hub; FRESH Initiative and the Healthy Bodegas and Green Carts (Greenmarkets, SNAP/Health Bucks); CookShop (cooking classes at Green Markets); and a Food Waste composting study. A recent change in the tax credit for green roofs allows roof top agriculture to qualify. However, there has been significant criticism that these laws do not begin to deal with the coming food crisis in New York City.

The most comprehensive study conducted on local food and its positive economic consequences was done in the state of Vermont by California Environmental Associates. Called Slow Money, Vermont field research and portfolio model WORKING DRAFT,[xxix] the Slow Money mission is to:

- Promote entrepreneurship that preserves and restores soil fertility, appropriate scale organic farming and local food communities.

- Catalyze increases in sustainable agricultural and environmental grant-making and mission-related investing by foundations; and

- Incubate next-generation socially responsible investment strategies, integrating principles of carrying capacity, non-violence, biodiversity, and care of the commons.

Primarily focused on Vermont dairy, meats, produce, tree fruit, and forest products, the study projects what a hypothetical Slow Money portfolio might look like, and the financial tools necessary to determine what the problems, challenges and solutions would be.[xxx] The study looked at trends including, but not limited to, the increasing price of land due to development pressures, lack of in-state processing infrastructure, and opportunities to help grow companies that are opening new markets and providing support to entrepreneurs who have the potential to scale up.

The Vermont study could serve as a model for one to be undertaken in the New York City Bioregion, quantifying our “farmshed,” food-based enterprises, and woodlands and other natural resources. The scale for this project and the financial commitment necessary to carry it out will obviously be orders of magnitude larger than what was forecast for Vermont in 2008[xxxi]

Other potentially scalable Foodshed strategies are:a project of the Northampton Food Security Group in Massachusetts. Feed Northampton:[xxxii]First Steps Toward a Local Food System is a food security plan prepared by graduate students at the Conway School of Landscape Design for a Transition Town community group in Northampton, Massachusetts;[xxxiii]Ground Up, Cultivating Sustainable Agriculture in the Catskill Region prepared by the Columbia University Urban Design Research Seminar,Upper Delaware Preservation Coalition, the Open Space Institute, and Catskill Mountainkeeper;[xxxiv] and Fresh Food for All an article by Elizabeth Royte in onearth magazine. [xxxv]

Funding and Investing in Food and the Bioregion’s New Economy[xxxvi]

Our economic system has failed in every dimension: financial, environmental, and social. Moreover the current financial collapse provides an incontestable demonstration that it is unable to self-correct.… The need is not to repair Wall Street but to replace it with institutions devoted to serving the financial needs of ordinary people in ways that are fair, honest, and consistent with the reality of our human dependence on Earth’s biosphere. [xxxvii]

When looking at the opportunities for investment in the New Economy for our Bioregion, one must also look at local capital available for building this infrastructure. Woody Tasch, a promoter of “Slow Money” and an author of a book of the same name has good advice for investors:

Socially responsible and sustainable investing directly in individual small food enterprises near where we live is the goal. Looking at philanthropy and investment through the lens of food, soil and place, we will find new ways to rebuild trust and to support millions of small acts of entrepreneurial care. There are many steps along the way.[xxxviii]

If we can create a dynamic in which small and large investors put a little funding into a lot of entrepreneurial smaller local businesses in the clean tech and food sector, we can take steps to save a reasonable quality of life during what could be a catastrophic transition. This investment strategy runs counter to the conventional venture capital approach of investing a lot in high risk/high return enterprises. The way forward now is investing a little in a lot of low risk/low return ventures. The idea is somewhat like microfinance[xxxix] without either the recipient or the investor being a not for profit. What we need in this New Economy is a balance of people, profit, and planet, and principles that include care for our neighbors and those with the least, care forthe environment, and a fair share of the resources provided by the Earth.

Playing a role will be: community land trusts, agriculture conservation easements, urban agricultural redevelopment, and “low tech” transportation funded by mission-related investments from charitable foundations, micro-finance, peer-to-peer lending, “crowd funding,” social venture capital funds, family offices, credit unions and Community Development Financial Organizations, and conventional to organic farmland private equity funds like Farmland LP, [xl] and Stewardship Farms[xli] that will preserve farmland as a long term investment.

The idea that we need a “new economy”—that the entire economic system must be radically restructured if critical social and environmental goals are to be met—runs directly counter to the American creed that capitalism as we know it is the best, and only possible, option. Over the past few decades, however, a deepening sense of the profound ecological challenges facing the planet and growing despair at the inability of traditional politics to address economic failings have fueled an extraordinary amount of experimentation by activists, economists and socially minded business leaders. Most of the projects, ideas and research efforts have gained traction slowly and with little notice. But in the wake of the financial crisis, they have proliferated and earned a surprising amount of support—and not only among the usual suspects on the left. As the threat of a global climate crisis grows increasingly dire and the nation sinks deeper into an economic slump for which conventional wisdom offers no adequate remedies, more and more Americans are coming to realize that it is time to begin defining, demanding and organizing to build a new-economy movement. [xlii]

The New Economy is an emerging system of values, practices, institutions, policies and laws that support an economy designed to maximize current wellbeing and social justice without sacrificing the natural world or the resources available to future generations.[xliii] Those advocating a transition to a New Economy support an evolution where the priority is to sustain people and the planet; where social justice and cohesion are prized; and peace, communities, democracy and nature all flourish.

The New Economy movement is a response to the systemic failure of the “old” economy. It is an economy in which real wealth – something that has intrinsic value – forms the basis for enterprises that provide for their employees, the community in which they are located, and make a profit for the owners.

The need is not to repair Wall Street but to replace it with institutions devoted to serving the financial needs of ordinary people in ways that are fair, honest and consistent with the reality of our human dependence on Earth’s biosphere.[xliv]

Wall Street and Main Street are names given to two economies with significantly different priorities and values that are often in competition. Wall Street is in the business of making money to make money. Any involvement in the production of real goods and services is an incidental byproduct. Once a company, even one that started bymaking a useful product, begins to sell shares through exchanges or to private equity investors it becomes an agent of Wall Street. As a former executive of Odwalla told David Korten, “So long as we were privately owned by the founders, we were in the business of producing and marketing healthful fruit juice products. Once we went public, everything changed. From that event forward, we were in the business of making money.”

Main Street is a very different place from Wall Street. My grandfather started a lumber company with a friend who owneda pushcart. They scavenged construction sites, pulled nails out ofand squared up any lumber they couldfind, and soldit for what it was – a recycled product.Later they built their company into a large wholesale/retail lumberyard, and eventually became one of the precursors to Home Depot, a do-it-yourself, self-serve regional hardware and lumber company. But what my grandfather and my uncles, who eventually took over the business, never forgot was that they had an obligation to their employees, many of whom worked at the company for their entire careers. They sold a good product, treated their customers with respect, supported their community, and made a living for their families. When my uncles retired, they sold the company to a Fortune 500 company and within 3 years it no longer existed. I tell this story because this Main Street business was locally owned, locally rooted, and privately held. It was innovative, successful, and sold tools, materials, and services to people who became repeat customers because of the quality and customer service they received. As soon as their company became the property of Wall Street, all those values were lost and destroyed.

Creating this kind of entrepreneurship with Main Street values is much more difficult today. There is no easy way to start a new local business that creates real wealth and something with intrinsic value, in part because it is difficult for individuals to put money into worthy small businesses in need of capital. Our financial markets have evolved to serve big business even though small enterprises create three out of every four jobs and generate half of GDP. If you add in other “place based” nonprofits, co-ops, and the public sector, it is nearly 58 percent of all economic activity. Why then are we not investing some 58 percent of our retirement funds in Main Street enterprises?[xlv]

Under our present system, no local businesses receive any of our pension savings, or investments in mutual funds, venture capital firms, or hedge funds. The result is that we who invest do so in Fortune 500 companies we distrust, and under-invest in the local businesses we know are essential for local vitality. We need new mechanisms to invest in local, place-based, and Main Street Businesses.

President Obama signed the JOBS Act in April 2012, opening up a new source of funding for small companies and start ups. Much of the attention so far has been on this component of the bill because it would allow financing via crowd funding.[xlvi]Participants can raise as much as $1 million a year without having to do a public offering – a step requiring state-by-state registrations that can cost thousands of dollars. The belief – and hope – is that this type of funding will open up more opportunities for capital to flow into startups. That, in turn, will help grow new companies and create new jobs.

Like the question Woody Tasch, founder of Slow Money asked:“What would the world be like if we invested 50% of our assets within 50 miles of where we live?”Amy Cortese, author of Locavesting, posits an additional question: If Americans have about $30 trillion invested, “imagine if half of that, $15 trillion, was invested in local communities rather than multinational conglomerates that are outsourcing jobs and not investing domestically. I think we’d be living in a far different world. That said, it is a little idealistic to think we’ll ever get to 50% any time soon. But even think about 10% or 5% or 1%. One percent of $26 trillion is $260 billion going to the Main Street economy and that’s a lot.….. (T)here is a very compelling case to be made for local investments as an asset class in a diversified portfolio.”

In a world of sprawling multinational conglomerates and complex securities disconnected from place and reality, there is something very simple and transparent about investing in a local company that you can see and touch and understand. As investing guru Peter Lynch has counseled, it makes sense to invest in what you know.[xlvii]

Main Street investing is how the local economy once functioned. It was in the interest of local well-off farmers, merchants, and small town banks to loan money to, and invest in, businesses that would hire local people, and make something that had value and created real wealth. In an attempt to replicate Main Street investing, the “spend local – hire local” movement has gained significant traction.

One reason for growing public interest in local investment is the spread of “buy local” campaigns, a movement that is more than just local hucksterism. Consider the title of an article in a recent issue of Time: “Buying Local: How It Boosts the Economy.” Cutting-edge economic developers (except at the national level) increasingly recognize the importance of strengthening locally owned, small businesses.[xlviii]

A well-run, buy local campaign that engages local businesses and citizens, can be a powerful tool for sustaining independent businesses and neighborhood-serving business districts. Buy independent / buy local[xlix] campaigns have exploded in recent years, bolstered by four annual surveys by the Institute for Local Self-Reliance.[l] The surveys showlarge benefits to independent businesses and communities from sustained campaigns by independent business alliances and similar organizations. Two groups, the American Independent Business Alliance, AMIBA [li]and the Business Alliance for Local Living Economies, BALLE[lii]are advocates for The Main Street economy and buy local/hire local campaigns.

Small towns like Stonington, ME,[liii] and large cities like Seattle, WA,[liv] have effective buy local and hire local campaigns. A New York City organization, Grow NYC,[lv] has a buy local food campaign. [lvi]Growing evidence suggests that every dollar spent at a locally owned business generates two to four times more economic benefit – measured in income, wealth, jobs, and tax revenue – than a dollar spent at a globally owned business. That is because locally owned businesses spend much more of their money locally and thereby pump up the so-called economic multiplier. Other studies suggest that local businesses are critical to tourism, walk-able communities, entrepreneurship, social equality, civil society, charitable giving, revitalized downtowns, and even political participation.

I work part of my week near Union Square in New York City. Determining what to buy for breakfast or lunch, or what to take home for dinner, is both convenient but difficult because of the amazing seasonal array of locally grown produce and baked goods. I’m also lucky to live in a small town where a new waterfront park, a vital arts organization, and a garden club have started to re-create the public space that is missing from most communities, and to actively support public participation in town beautification, as well as helping to feed those in need as part of the fabric of the community. We had two simple criteria for moving to our small New Jersey Raritan Bayshore town – a library within walking distance, and a local hardware store. We got that and much more. Even in the wake of the destruction wrought by Sandy, my town is a real “place,” it feels like home, and perhaps best of all, it helps me to have a positive sense of what is possible.

The Occupy movement[lvii]was absolutely right in saying the system is broken, greedy, and unfair. We urgently need to replace the current system with one that reasserts the right to a safe, healthy, productive environment for all; where “environment” is considered in its totality, inclusive of ecological, physical (natural and built); social, political, aesthetic, economic environments; and environmental justice. In the new system, the rights of individuals and groups must be equally preservedand respected in a way that provides for self-actualization and personal and community empowerment.[lviii]A community in which poverty and inequity are considered acceptable will always be prone to environmental and economic crises.

Transition,[lix] Power Down,[lx] and Re-localization[lxi] for Community Resilience

Emerging at the other end, we will not be the same as we were; we will have become more humble, more connected to the natural world, fitter, leaner, more skilled and, ultimately, wiser.[lxii]

Maintaining “business as usual” is no longer an option. The New York City Bioregion must face up to the unfolding crises. We cannot ignore obvious breakdowns in our society’s support system. Resilient communities are at the core of a successfulresponse to peak oil, climate change, and economic disruption. If we don’t plan for more robust communities, and implement solutions for pressing, indisputable problems, a catastrophic crash is inevitable. Crisis can equal opportunity as we saw during the Great Depression and during World War II. However unless sensible plans to manage disaster are formulated and put forward now, the opportunity afforded by crisis could be hijacked by a more organized well-financed minority with an authoritarian agenda.

There is a critical role for government in meeting the crises.[lxiii] Federal, state, and municipal governments must pass groundbreaking legislation,[lxiv] initiate proactive crisis management plans, and be prepared to respond to sudden emergency disruptions in transportation, food distribution, unprecedented joblessness and economic chaos. But unless a re-localization process parallels or precedes any government programs, there will be incomparable upheaval. Local resilience is the cornerstone of preparation for a post carbon, climate impacted, and a steady state economy.

We must use the Peak Everything crisis as an opportunity to address broader social and ecological issues – generating ideas that are inspiring, creative and attractive visions of revitalized local economies, visions grounded by a connection to place and to people. What sets these ideas apart from many earlier approaches to sustainability is a palpable determination to be realistic and viable, to involve everyone in the community, to capture the imagination, and to succeed.[lxv]

The Transition movement represents one of the most promising models available to us for engaging people and communities, to achieve the far-reaching actions required to mitigate the effects of peak oil, climate change and the economic crisis. Furthermore, Transitionre-localization efforts are designed to result in a life that is more fulfilling, more socially connected and more equitable than the one we live today – moving into the Ecozoic[lxvi] Era, as Thomas Berry says.

The Transition model is based on a loose set of real world principles and practices built up over time through experimentation and observation by Transition communities around the world as they drive forward to reduce carbon emissions and build community resilience. Underpinning the model is recognition of the following: peak oil, climate change and the economic crisis require urgent action;a world with less oil is inevitable so adaptation now is essential;it is better to plan and be prepared, than be taken by surprise;industrial society has lost the resilience to cope with shocks to its systems so we must act together now to work our way down from the “peak”; using all of our skill, ingenuity and intelligence, our home-grown creativity and cooperation,we canunleash the collective genius within our communities, leading directly to a more abundant, connected and healthier future for all.

Individuals, organizations, community development and environmental organizations, and citizens involved in planning and redevelopment efforts in local communities must step into leadership positions. We need to start working now to mitigate the effects of peak oil, climate change, and the economic crisis. Through re-localization, communities (and neighborhoods in larger cities) can “power-down and be lifeboats,” becoming local examples that can be replicated regionally. These functional relationships, ethics, and principles can begin to be implemented by:

- Forming a Transition New York City Bioregion umbrella organization under which other Transition town and neighborhood groups can gather, holding town meetings, providing cohousing opportunities in walk-able and bike-able neighborhoods, establishing food and tool coops, creating urban agriculture and community gardens, and many other initiatives.

- Growing more local food and supporting regional farming though farmer training and apprenticeships, farmland preservation, rezoning, tax relief, and community and restaurant supported agriculture.

- Reorganizing businesses in eco-industrial parks.[lxvii]

- Investing in and participating in alternative energy utilities.[lxviii]

- Building and retrofitting homes and commercial buildings for energy efficiency.

- Developing regional low carbon transportation for goods and people – hybrid and electric trucks and automobiles as a temporary fix, alternative fuel transit, hybrid electric sailing cargo vessels and ferries, and pedal power.

- Creating recycle banks, “free stores,” farmer’s markets and “Small-mart”[lxix]business festivals, (get to know your farmer, processor, and purveyor), block parties, local celebrations of the seasons, local arts and music organizations, and food pantries supplied by community gardens.

- Exploring local currency, “Slow Money[lxx] investing,” and banking alternatives such as Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI),[lxxi] credit unions and investment clubs[lxxii]

- Growing social venture capital,[lxxiii] for benefit[lxxiv] for profit companies, and “resilient philanthropy.”[lxxv]

- Rethinking economic development for resilience through investment in food-shed preservation, local food, and food distribution infrastructure.

- Developing local and regional energy descent plans.[lxxvi]

- Electing/appointing local officials who will lead the community to resilience or developing new methods of governance.

Planning a Post Carbon Future for New York City and its Bioregion

Green urbanization utilizing collective intelligence will assist a needed turnaround from our current plight. Instead of needlessly facing the brink of a volatile future completely unprepared, we are beginning to experience how the whole is indeed greater than the sum of its individual parts.[lxxvii]

It is time to gather the brightest most committed people from the New York/New Jersey/Connecticut/and Pennsylvania bioregion for a charrette,[lxxviii] an “open space”[lxxix] dialogue, or an Orton Family Foundation[lxxx]style“Heart and Soul” analysis that harnesses the ability of citizens to imagine and achieve a better future for themselves and their community.[lxxxi] Conveners should include but not be limited to David Korten,[lxxxii] Michael Shuman,[lxxxiii] James Hansen,[lxxxiv]Woody Tasch,[lxxxv]Amy Cortese,[lxxxvi] Alex Steffen,[lxxxvii]Richard Heinberg,[lxxxviii]Chris Martenson,[lxxxix]Bill McKibben,[xc]Paul Greenberg,[xci] Adam Yarinsky,[xcii] Susanna Drake,[xciii]Paul Hawken,[xciv]Betsy Rosenbluth,[xcv]Roy Morrison,[xcvi] David Ehrenfeld,[xcvii] Thomas Friedman,[xcviii]Gus Speth,[xcix] Van Jones [c]Jason McLennan,[ci] Will Allen,[cii]Carolyne Stayton,[ciii]and many others[civ]. They will help guide us in developinga comprehensive plan for A Bright Green New York City Bioregion – a new, secure, sustainable, slow money, small business, main street economy, focused on local energy and food, and its economic, social, and environmental consequences.

The participants in this vital exercise – entrepreneurs and social venture capital investors; planners and co-housing/eco village developers; Transition Town advocates, permaculturists and foodshed advocates; charitable foundations and futurists; students and union members; fishermen and environmentalists; economists and climatologists; traditional, organic and biodynamic, rural, suburban, and urban farmers; government and local businesses – will propose and develop mutually beneficial, implementable ideas to mitigate the impending crises, and prepare us for A Bright Green Future.

The two seminal questions for the first proposed charrette and open space planning session, should be:

- How can the New York City metropolitan area develop a food security plan to feed itself and neighboring communities from farms within 100 miles of the Battery? And how do we re-connect New York City, not just to its watershed but to its “farmshed?”

- Should we commit $10-15 billion to construct wetlands and oyster reefs, enforce flood hazard building restrictions, plan for a retreat from flood hazard areas, and appropriately place sea gates needed to protect New York City, coastal New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut’s vulnerable infrastructure?

The New York City Bioregion must redefine its relationship with farmers by preserving farmland. Through an agreement similar to the one protecting New York City’s Watershed[cv]we can protect New York’s Hudson Valley and the Catskills; and the New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut farm-shed. This can be achieved through groups like the Open Space Institute,[cvi] Natural Resources Defense Council,[cvii] Trust for Public Land,[cviii]The Nature Conservancy,[cix]and Conservation Resources.[cx]

The people and their representatives must also recommit to the restoration of the NY/NJ Harbor Estuary, The Hudson River, Long Island Sound and coastal resources in the region working with the informed and engaged scientific, engineering, and non-governmental-organizations[cxi] to develop short, mid, and long term mitigation plans[cxii] to protect valuable natural resources and human infrastructure endangered by sea level rise, and the “new” normal storms likely to continue to affect our Bioregion.[cxiii]

Together we can create a Transition New York City Bioregion organization to deal with the challenges of population growth; energy consumption; food needs; and human impacts on the environment. This organization will have the visionary leaders, a committed board, and the means to advocate, educate, lobby, and create by example enterprises and institutions to provide the tools for re-skilling individuals, re-localizing agriculture and commerce, re-empowering Main Street, creating low tech transportation alternatives, mitigating climate change, and advocating for a “Green New Deal”(jobs, universal health care, and peace), and The New Economy – all vital for our survival in a post carbon world.

The best hope for a new political dynamic is a fusion of those concerned about environment, social justice, and political democracy into one progressive force. A unified agenda would embrace a profound commitment to social justice and environmental protection, a sustained challenge to consumerism and commercialism and the lifestyles they offer, a healthy skepticism of growth-mania and a new look at what society should be striving to grow, a challenge to corporate dominance and a redefinition of the corporation and its goals, and a commitment to an array of major pro-democracy reforms.[cxiv]

To achieve our goal, we must embrace a bigger, more open-hearted, view than the one held by stock traders and politicians. We need a post-growth/post-carbon economy that works for all people and all of nature: a bioregional re-localized economy based on renewable resources harvested at nature’s rates of replenishment, not a fossil-fueled global economy driven by the imperative of ever-higher returns on investment.

There will be life after the age of “limitless growth,” and it will be a better life if our Bioregion’s priority is our people and the integrity of the biosphere, rather than high stock prices, corporate profits, and the reckless wasting of irreplaceable natural resources. I invite you to join me on this challenging but exhilarating journey to develop and implement pragmatic positive change for New York City and its Bioregion – to hospice the end of one era and midwife the beginning of another.

Thank you for reviewing this document and please provide me with feedback, advice, and criticism. I also hope you will take the next very large step beyond sustainabilitysothat we can travel together into A Bright Green Future.

Andrew Willner, Sustainability Solutions, andrew.willner@gmail.com, www.andrewwillner.com

[i]The Great Turning, From Empire to Earth Community, Yes Magazine, May 8, 2006, David Korten.

[iii]Power Down, Richard Heinberg.

[v]The End of Growth, Richard Heinberg, page, 280-281

[vi]The Transition Handbook: from oil dependency to local resilience – by Rob Hopkins

[vii]Permaculture is a branch of ecological design and ecological engineering which develops sustainable human settlements and self-maintained agricultural systems modeled from natural ecosystems. The core tenets of Permaculture are:

• Take Care of the Earth: Provision for all life systems to continue and multiply. This is the first principle, because without a healthy earth, humans cannot flourish.

• Take Care of the People: Provision for people to access those resources necessary for their existence.

• Share the Surplus: Healthy natural systems use outputs from each element to nourish others. We humans can do the same. By governing our own needs, we can set resources aside to further the above principles.

Permaculture draws from several disciplines including organic farming, agroforestry, integrated farming, sustainable development, and applied ecology. “The primary agenda of the movement has been to assist people to become more self reliant through the design and development of productive and sustainable gardens and farms. The design principles which are the conceptual foundation of Permaculture were derived from the science of systems ecology and study of pre-industrial examples of sustainable land use.“[5]

Permaculture design emphasizes patterns of landscape, function, and species assemblies. It asks the question, “Where does this element go? How can it be placed for the maximum benefit of the system?” To answer this question, the central concept of Permaculture is maximizing useful connections between components and synergy of the final design. The focus of Permaculture, therefore, is not on each separate element, but rather on the relationships created among elements by the way they are placed together; the whole becoming greater than the sum of its parts. Permaculture design therefore seeks to minimize waste, human labor, and energy input by building systems with maximal benefits between design elements to achieve a high level of synergy. Permaculture designs evolve over time by taking into account these relationships and elements and can become extremely complex systems that produce a high density of food and materials with minimal input.[6]

Permaculture is an approach to designing human settlements and agricultural systems that is modeled on the relationships found in nature. It is based on the ecology of how things interrelate rather than on the strictly biological concerns that form the foundation of modern agriculture. Permaculture aims to create stable, productive systems that provide for human needs; it’s a system of design where each element supports and feeds other elements, ultimately aiming at systems that are virtually self-sustaining and into which humans fit as an integral part.

Common Permaculture practices include the use of agroforestry, natural building, rainwater harvesting, and sheet mulching.

[viii]Transitionus.org/why-transition

[x] Our health and wellbeing depends upon the services provided by ecosystems and their components: water, soil, nutrients and organisms. Therefore, ecosystem services are the processes by which the environment produces resources utilized by humans such as clean air, water, food and materials. Ecosystem services can be defined in various ways. The Millennium Ecosystem Assessment provided the most comprehensive assessment of the state of the global environment to date; it classified ecosystem services as follows:

- Supporting services: The services that are necessary for the production of all other ecosystem services including soil formation, photosynthesis, primary production, nutrient cycling and water cycling.

- Provisioning services: The products obtained from ecosystems, including food, fiber, fuel, genetic resources, biochemicals, natural medicines, pharmaceuticals, ornamental resources and fresh water;

- Regulating services: The benefits obtained from the regulation of ecosystem processes, including air quality regulation, climate regulation, water regulation, erosion regulation, water purification, disease regulation, pest regulation, pollination, natural hazard regulation;

- Cultural services: The non-material benefits people obtain from ecosystems through spiritual enrichment, cognitive development, reflection, recreation and aesthetic experiences – thereby taking account of landscape values;https://www.ecosystemservices.org.uk/ecoserv.htm

[xi] The long-term cross-cultural studies of economist Manfred Max-Neef suggest that fundamental needs fall into nine universal categories: subsistence, protection, affection, understanding, participation, idleness, creation, identity, and freedom. A Conservation Economy is structured to meet these needs for all people. Household Economies, Local Economies, and Bioregional Economies ensure that these needs are met as locally as possible.

A regional food system provides healthy food from reliable regional sources, minimizing food imports of unpredictable price and quality. It emphasizes broad access to food resources across the landscape, and stable land tenure for farmers and fishing rights for fishermen. It treats food security – availability of affordable, healthy food – as a fundamental right.

Health is the most fundamental need of all, and the health of people is utterly dependent on broader Ecosystem Services like pure water, clean air, fertile soil, habitat for food production, a stable climate, and many others. These ecosystem services must be properly maintained as an investment in public health. In addition, a wide range of health care modalities (e.g. Western, Eastern, Naturopathic) should be made available at affordable cost.

Shelter for All implies that a wide range of housing types is available, with an emphasis on sufficient levels of affordable and healthy housing. In a conservation economy, there are abundant opportunities for people of all ages to have Access to Knowledge in order to develop new skills and livelihoods, participate in Civic Society, and deepen their Sense of Place.

Fundamental needs are best met in ways that build Community and Social Capital. They are the foundation for human development. An emphasis on fundamental needs leads to a sufficiency for all rather than an excess for a few. This in turn reduces resource consumption while greatly enhancing the quality of life. As work is aligned more and more closely with genuine needs, it gains meaning and becomes more joyful.

© Ecotrust, 2002

[xii]Designers and decision-makers too often define problems narrowly, without identifying their causes or connections. This merely shifts or multiplies problems. Systems thinking—the opposite of that dis-integrated approach—typically reveals lasting, elegantly frugal solutions with multiple benefits, which enable us to transcend ideological battles and unite all parties around shared goals.

Our lives are embedded in systems: families, communities, industries, economies, ecosystems. The machines we rely on are also systems, which have increasingly profound effects on the human and biotic systems around them. https://www.rmi.org/sitepages/pid62.php

[xiii]Natural capital is the extension of the economic notion of capital (manufactured means of production) to goods and services relating to the natural environment. Natural capital is thus the stock of natural ecosystems that yields a flow of valuable ecosystem goods or services into the future. For example, a stock of trees or fish provides a flow of new trees or fish, a flow which can be indefinitely sustainable. Natural capital may also provide services like recycling wastes or water catchment and erosion control. Since the flow of services from ecosystems requires that they function as whole systems, the structure and diversity of the system are important components of natural capital.

[xiv]https://www.mg.co.za/article/2007-05-10-danish-island-leads-the-way-in-clean-energy

[xv]Materials and waste exchanges are markets for buying and selling reusable and recyclable commodities. Some are physical warehouses that advertise available commodities through printed catalogs, while others are simply Web sites that connect buyers and sellers. Some are coordinated by state and local governments. Others are wholly private, for-profit businesses. The exchanges also vary in terms of area, service and types of commodities exchanged. In general, waste exchanges tend to handle hazardous materials and industrial process waste while materials exchanges handle nonhazardous items. Typically, the exchanges allow subscribers to post materials available or wanted on a Web page listing. Organizations interested in trading posted commodities then contact each other directly. As more and more individuals recognize the power of this unique tool, the number of Internet-accessible materials exchanges continues to grow, particularly in the area of national commodity-specific exchanges. Wherever possible, the materials exchange programs presented contain a brief description of the services offered, including the materials available for exchange, how to contact the exchange, and other pertinent information. Significant effort has been made to provide a comprehensive and accurate list of materials exchanges; however, this Web site may not currently represent a complete listing of national, regional, and local exchanges. USEPA Web Site

[xvi] The objective behind tax shifting is to stop taxing the things we want (like income and savings) and shift towards taxing things people collectively do not want (like waste and pollution). The current tax system encourages depletion of natural resources and the unsustainable degradation of the environment, while discouraging job creation. Ideally, a shift toward taxing unwanted effects over desired ones, without increasing the total tax burden, will use market mechanisms to influence and reward more sustainable behavior without more government regulations.

Resources:

Hunter, L. 2009. Tax Shifting. Alternatives, Environmental Ideas and Action. Retrieved March 14, 2011, fromhttps://www.alternativesjournal.ca/articles/tax-shifting

Hartzok, A. [n.d.) Financing Local to Global Public Goods: An Integrated Green Tax Shift Perspective. Earth Rights Institute. Retrieved March 14, 2011, from https://www.earthrights.net/docs/financing.html

[xvii]an ecologically ideal region or form of society

[xix] Percival Alfred Yeomans (P.A.) was born in Harden N.S.W. in 1905.Yeomans undertook the design and construction of a different concept in cultivation equipment. He solved the need for better equipment than the chisel plow to deeply loosen soil without bringing up the subsoil. This equipment was the first rigid shanked vibrating sub-soil cultivating ripper for use with farm tractors. It is many times more efficient than a chisel plow, and is able to loosen more soil to a greater depth using less tractor power. The backbone, the veritable vertebrae, of Yeomans’ Keyline Design system, and the outcome of fifteen years of adaptive experimentation in a broad-acre environment characterized by dynamic uncertainty, (4) is Yeomans’ Keyline Scales of Permanence (KSOP).

- Climate

- Landshape

- Water Supply

- Roads/Access

- Trees

- Structures

- Subdivision Fences

- Soil

Using the Keyline Design System in planning, development, and management decision-making is a matter of consciously designing various factors to ‘fit’ into their given context. A matter of matching the horsepower to the cart! Of fitting the house atop the foundation. Yeomans gives the ‘everyman’ example that one will normally buy a tie to match the suit and not vice versa! How much more important when dealing with whole livelihoods and landscapes! This is why order is important.

[xx]Roseland, Mark (1997). “Dimensions of the Eco-city”. Cities 14 (4): 197–202.

[xxi]Chris Martenson, The Crash Course

[xxii]https://vgncds.bsu.edu:82/greening/article/0,,52588–,00.html

[xxiv]“Food Localization as Economic Development,” Capitalizing the Local Food Shift

[xxv]https://www.farmland.org/programs/states/ca/Feature%20Stories/San-Francisco-Foodshed-Report.asp

[xxix]https://www.slowmoneyvermont.com/img/slowmoneyvt_invest_thesis.pdf

[xxx]The study proposed a total fund size of $100 million with a 15 year life, divided into growth capital for farm & food based enterprises ($33 million), farmland real estate investing ($33 million), and sustainable forest land investing ($33 million). Additional investment possibilities included: standard debt for established businesses, loan guarantees, micro-working capital loans for small-scale agriculture, and eco-system services (e.g., carbon sequestration, water, and biodiversity).

[xxxi]A NYC bioregional plan would need to include the following guiding principles: