New York City and its periphery host a $1.5 trillion economy, central to a world economy of about $100 trillion. Four hundred years ago, New York Harbor, and the Bay beyond it, was in a state of equilibrium with its human population; oysters filled the harbor bottom, and the surrounding hills and wetlands teemed with wildlife.

The eight million inhabitants of New York help define successful modern life around the globe, and at the same time, the coastal geography of the city puts New York on the front line of climate change and our civilization’s sustainability challenge. Research in the past few years shows that for New York, ‘sustainability’ has become a literal question.

This week, the New York Times reported on a new paper projecting sea level rise from potential ice loss in Antarctica: “The long-term effect would likely be to drown the world’s coastlines, including many of its great cities.” If so, New York would not have another 400 years.

The answer comes in how we change, or choose not to change.

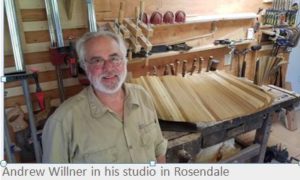

Andrew Willner has been a leader of efforts to protect the waterways and land in New York and New Jersey for over twenty five years. Willner founded New York/New Jersey Baykeeper in 1989, running the organization till 2008. In recent years, science and policy have been catching up with his vision for a sustainable harbor. Ana Deustua interviewed him for City Atlas.

Why did you create the New York/New Jersey Baykeeper?

With a friend from South Street Seaport, I started a small boat building and repair yard on Staten Island. My daughter, who was 10 years old, came to the yard and it made me angry that she probably shouldn’t go swimming in the waters of Staten Island because of pollution. It infuriated me. I became angry at the idea that a beautiful body of water could be detrimental to my daughter’s health if she went swimming. I swam in it, but I didn’t want my child to swim in it.

I found out that there was a Riverkeeper on the Hudson River, a Soundkeeper in Long Island, and Baykeepers in Delaware and San Francisco. I began communicating with them and they helped me get the Baykeeper program started in the summer of 1989. I worked with Baykeeper for twenty years, until April 2008. It was a great opportunity for me, I really treasured it and it was the biggest challenge I have ever had.

What was your biggest accomplishment while running Baykeeper?

The biggest change since I was appointed baykeeper is that people didn’t see the New York Harbor as a natural resource. If I did anything in the 20 years that I was the baykeeper, it’s that we converted hundreds of thousands to think of the lower Hudson, the East River, New York Bay, Jamaica Bay, and Raritan Bay as their watery homes: places where they can go for recreation, fishing, and where they would identify with the waterfront within their community.

The waterfront has become one of the most appealing places to live. How is this trend changing the New York/New Jersey harbor estuary?

This race to the coast has several negative implications. More people and property are in harm’s way in storm surge and flood prone areas, the “centers” of older waterfront communities are being eroded in favor of the water’s edge, and the loss of “working waterfront” is a detriment to the region as a whole. Some people with means, and the developers on water’s edge buildings, will get an exclusive view and make a short term profit, while ultimately the externalities of sea level rise, storm ravages, and lack of planning and foresight are costs which will be borne by the rest of us. The other major problem is that privatization of the waterfront excludes the public from their commonly owned, public trust resources, to the advantage of the privileged few.

Would you let your daughter now swim in the Bay?

My daughter is now a Mom, and a physician. I can advise her but she is probably more equipped to determine whether or not, or where she and her children should swim. However, I continue to enjoy swimming in a variety of locations.

Are we prepared to keep New York Bay clean, as a rising sea level reaches inland?

I don’t think so. For example, most sewage treatment plants are in the floodway and may become inoperable. Toxic waste sites and garbage landfills will be underwater, petroleum and oil facilities are located on the waterfront and will be adversely affected by sea level rise, and abandoned businesses and residences will pollute the estuary for a very long time unless timely actions – including retreat from the shore – are instituted immediately. I am however fairly confident that none of this will be done in a timely way.

Why should New York lead the talk on sea level rise?

New York City, being an island metropolis, is also projected to be one of the five U.S. cities hardest hit by climate change and most vulnerable to rising sea levels. Likewise, our metropolis produces little of its own food and little else for its people’s basic needs. This puts our city and its surrounding communities in serious jeopardy.

New York is a coastal city and region. The very reasons it became an important port are now the things that will adversely affect the region’s infrastructure and people. On the positive side – “ If it can happen here it can happen anywhere.”

How did your work as baykeeper lead you to your current work?

During my work with New York/New Jersey Baykeeper from 1989-2008 I met and engaged with thousands of people from all walks of life and from all parts of the harbor. When I retired from Baykeeper I started a sustainability consulting firm to continue the work I was doing with environmentally conscious businesses, municipalities, and non-profit organizations.

Tell us your three steps to make the New York bioregion more resilient to climate change.

1. Become a leader in sustainability and resilience.

2. The people have to make their elected officials take action.

3. Be aware that real pain is associated with the changes needed to mitigate and avoid the effects of sea level rise and climate change.

Resilient communities are at the core of a “Too Small to Fail” future. If we don’t plan for more robust communities, and implement solutions for undeniable problems, a catastrophic crash seems inevitable. However crisis can equal opportunity, as we saw during the Great Depression and during World War II. But unless sensible plans to manage disaster are formulated and put forward now, the opportunity afforded by crisis could be hijacked by a more organized well-financed minority with an authoritarian agenda.

You’re an advocate for the Transition Town concept of a resilient, locally-based economy. Is New York City, with a population of 8 million, really a candidate for the Transition idea?

In short the answer is probably not. However, neighborhoods and coherent sections of the city, where urban agriculture, core community groups, and like-minded people are already intact, may be.

Here is what the “New Economy” for our bioregion might look like: it will prosper through an eclectic amalgam of business, non-profit and government innovation, including rooftop solar warehouses, wind farms, and tidal energy producers; urban and rural farmers, and rooftop apiaries; commercial fishermen, fish mongers, and fish farmers; local farmers markets, shoreline farmers, and seafood markets; a local water-based transportation system to bring goods to market; suburbia converted to interconnected “front yard” farms; a local currency used to pay for local commodities; buying and hiring locally; restored and created wetlands serving as nurseries for fish and wildlife and where blueberries and other produce can be sustainably harvested; sustainable forests that are logged selectively with an eye on future production; public works projects such as sea walls and sea gates as required to protect communities and valuable infrastructure against sea level rise; an economy of local businesses and micro-industries, including everything from brewers and butchers to cheese makers and toolmakers; from ship builders to bicycle builders; local wind turbine, solar collector, and tidal generator manufacturers and installers; shoemakers and fix it shops; composters and oil recyclers.

If we become a locally-focused region, what happens with the foods and products that can’t be grown or produced here?

The New York City bioregion is [already] connected tenuously to the rest of the world by literally thousands of lifelines, including an aging and increasingly failure-prone power grid; an aging and leaky water system; and a vast network of roads, rails, shipping and air routes that rely exclusively on increasingly costly fossil fuels. Like a patient on intravenous life support, any major interruption in the flow of natural resources, energy, water or food to the metropolitan area could hamstring or permanently harm its economy and people. With global oil, gas and coal production predicted to irreversibly decline in the next 10 to 20 years, this collapse becomes not a question of if, but when.

Most of the products we consume in New York City come from Asia or Europe, or by truck from California and the mid-west. New York is tied to these lifelines that extend around the world for fuel, but, when petroleum becomes too expensive to transfer, it’s going to be a crisis if we don’t get alternative sources. So food, energy and water are critical in the New York City region.

What would happen if the Transition Town approach worked in New York City?

It will demonstrate that it can work anywhere else.

What are the advantages of the ‘Main Street economy’ versus a ‘Wall Street economy’?

My grandfather started a lumber company with a friend who owned a pushcart. They scavenged construction sites, pulled nails out of and squared up any lumber they could find, and sold it for what it was – a recycled product. Later they built their company into a large wholesale/retail lumberyard, and eventually became a self-serve regional hardware and lumber company. But what my grandfather and my uncles, who eventually took over the business, never forgot was that they had an obligation to their employees, many of whom worked at the company for their entire careers. They sold a good product, treated their customers with respect, supported their community, and made a living for their families. After my uncles retired, their partner sold the company to a Fortune 500 company and within a few years it no longer existed.

I tell this story because this Main Street business was locally owned, locally rooted, and privately held. It was innovative, successful, and sold tools, materials, and services to people who became repeat customers because of the quality and customer service they received. As soon as their company became the property of Wall Street, all those values were lost and destroyed. Until then it had been too small to fail.

Growing evidence suggests that every dollar spent at a ‘too small to fail’ locally owned business generates two to four times more economic benefit – measured in income, wealth, jobs, and tax revenue – than a dollar spent at a globally owned business. That is because locally owned businesses spend much more of their money locally and thereby pump up the economic multiplier.

Under our present system, no local businesses receive any of our pension savings, or investments in mutual funds, or investment from venture capital firms, or hedge funds. The result is that we who invest do so in Fortune 500 companies we distrust, and under-invest in the local businesses we know are essential for local vitality. We need new mechanisms to enable investment in local, place-based, ‘too small to fail’ Main Street businesses.

Main Street investing is how the local economy once functioned. It was in the interest of well-off farmers, merchants, and small town banks to loan money to, and invest in, businesses that would hire local people, and make something that had value and created real wealth. Perhaps, along with a ‘buy local/hire local’ campaigns, ‘locavesting,’ – a resurgence of local currencies, and new public and community banks, and credit unions will reinvigorate our region’s Main Street economy.

How do social justice and environmental sustainability intersect?

Any plan for a resilient bioregional economy must insure that everyone has fundamental needs met for nutritious food, shelter, healthcare, education, and ecosystem services as a non-negotiable condition. This means such things as converting urban brownfields to greenfields, ensuring affordable housing, improving work opportunities for disadvantaged groups, and allowing seniors and children to play useful civic roles.

You posted a letter and proposal in 2013 called “A Call to Action.” In it you describe the risks of climate change in New York City and the benefits of the Transition movement. In three years since, what has changed?

Everything I wrote about in 2013 is coming true more quickly than I could have imagined, except for the response to the dire problems facing the region.

Willner is founder of New York/New Jersey Baykeeper (courtesy Andrew Willner)

An exhibit at the Wired Gallery, 11 Mohonk Road, High Falls, NY

An exhibit at the Wired Gallery, 11 Mohonk Road, High Falls, NY Jo-Ellen was born in Huntington, Long Island, in 1947 and grew up in Setauket, Long Island. She attended the State University of New York, New Paltz, during which time she focused on dollmaking. Also, at that time, Trilling began creating portrait figures in cloth, producing prototypes for her later works. She moved to New York City in 1972 where she studied pastel drawing at New York’s Art Students League with Dan Green.

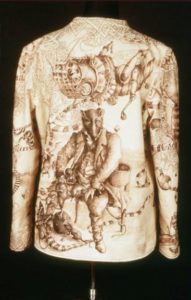

Jo-Ellen was born in Huntington, Long Island, in 1947 and grew up in Setauket, Long Island. She attended the State University of New York, New Paltz, during which time she focused on dollmaking. Also, at that time, Trilling began creating portrait figures in cloth, producing prototypes for her later works. She moved to New York City in 1972 where she studied pastel drawing at New York’s Art Students League with Dan Green. Fashioned from cloth, wire, and other materials, her sculptures portray such subjects as lascivious pigs in flamenco costume and leering dogs in gangster suits or leather motorcycle outfits. Trilling’s sculptures have been exhibited at various venues. They may be found in the Topeka and Shawnee County Public Library, Kansas, and the Ito Doll Museum, Japan. Trilling began painting in 2001, and her first exhibition devoted to her oils in New York City took place in 2008.

Fashioned from cloth, wire, and other materials, her sculptures portray such subjects as lascivious pigs in flamenco costume and leering dogs in gangster suits or leather motorcycle outfits. Trilling’s sculptures have been exhibited at various venues. They may be found in the Topeka and Shawnee County Public Library, Kansas, and the Ito Doll Museum, Japan. Trilling began painting in 2001, and her first exhibition devoted to her oils in New York City took place in 2008.